Preserving Nihonmachi

In their new book, Mary Hanneman and Lisa Hoffman share the history of Tacoma's Nihonmachi and the Japanese Language School once located on what is now the UW Tacoma campus.

This Section's arrow_downward Theme Info Is:

- Background Image: ""

- Theme: "light-theme"

- Header Style: "purple_dominant"

- Card Height Setting: "consistent_row_height"

- Section Parallax: ""

- Section Parallax Height: ""

UW Tacoma faculty members Lisa Hoffman and Mary Hanneman didn’t know each other when they answered a university email related to the Japanese Language School. The school — known as Nihongo Gakko — once sat on the 1700 hundred block of South Tacoma Avenue near the what is now the western edge of campus.

The UW purchased the structure in 1993, as part of the initial assemblage of land for the then-new UW Tacoma campus. By 2004, a team of architectural consultants hired by the campus determined the building couldn’t be restored and should be demolished due to safety concerns. “University leadership put out a call to faculty that asked if anyone was interested in pursuing a project about this,” said Hanneman. “We felt a responsibility to make sure these voices were heard and should be a part of the public historical record,” Hoffman added.

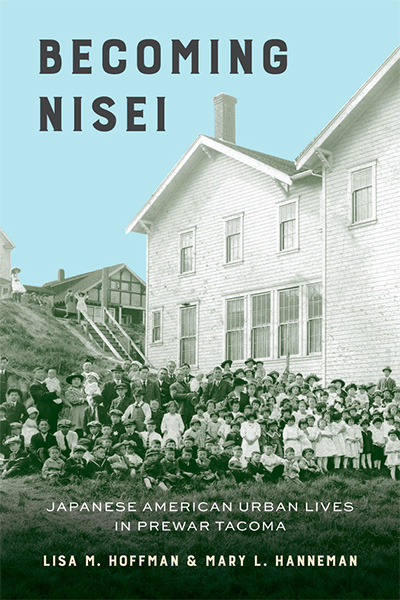

Hanneman and Hoffman embarked on a project to document the experience of the Japanese community in Tacoma including those who lived in the Nihonmachi or “Japantown,” an area that extended from South 19th Street to South 11th Street between Pacific Avenue and Market Street. The pair interviewed more than 40 Nisei (second-generation American-born children of Japanese immigrants) for their recently released book “Becoming Nisei: Japanese American Urban Lives in Prewar Tacoma.”

The book looks at the lives of Tacoma Nisei from transnational as well as spatial perspectives. Tacoma Nisei negotiated multiple positions that were not just about being Japanese or American. For instance, on the one hand they were American citizens, but they were still expected to retain their Japanese heritage through the adoption of Meiji-era cultural practices and ethics. “The Japanese migrants in this case didn’t just leave their nation and their identity behind,” said Hanneman. “They didn’t come to new country and say, ‘Here we are, we’re Americans.’”

The relatively small size of the Tacoma Japanese American community meant neighbors knew each other. Hanneman and Hoffman describe the community of less than 1,000 as close knit. Most lived in the Nihonmachi but there were also pockets on the tideflats and South Tacoma Way. The relatively small size of the Nihonmachi produced something Hoffman calls a “walking scale” life. “We’re talking about a concentrated area,” said Hoffman. “The sidewalks provided Nisei with a sense of belonging. There’s also something interesting around this idea that their own sense of identity and self is being constituted through their experience with the city.”

Hanneman and Hoffman recently appeared on the UW Tacoma podcast Paw’d Defiance to discuss their book. Below are some excerpts from the conversation, which have been edited for length and clarity.

Eric Wilson-Edge: You say something interesting about Nisei seeing themselves as Tacoma Japanese. Could you talk about that concept?

Dr. Mary Hanneman: I think that the experience of incarceration, I feel like from the interviews, was a moment that the Tacoma Japanese recognized their identity as Tacoma Japanese. They had this unique Tacoma culture. They all knew each other. You had to bow to this shopkeeper when you passed. If you saw any Japanese anywhere in Tacoma, you bowed because you knew them. And then to see that that was not the case when they encountered other Japanese in the camps became this moment of coming face-to-face with an identity that's not really set.

Dr. Lisa Hoffman: That's a really important point, that as they were describing what it meant to grow up in Tacoma, they would often reference their experience when they first started meeting Japanese from other parts of the country and how they seemed different. This is where it comes back to their experience at the language school. The teachers were so dedicated, it was a daily experience in Tacoma, not just once a week or just on weekends. There was only one Japanese language school in the city and it was secular. So many of the other cities along the West Coast and in Hawaii had multiple language schools, and they were started and run by the different religious organizations. So here while the Issei [those born in Japan who were the first generation of immigrants to North America] may have been committed to their prefectural identities and the different religious associations, the children all got to know each other through the language school experience.

Wilson-Edge: Most of the buildings from this era are gone. What happened?

Hanneman: I think the fact that these buildings disappeared, this built environment disappeared, it's not just by chance, it's not just development. These buildings were vacated with incarceration. And what happened? The businesses are gone, what happens to the buildings? They fall into neglect and disrepair. So, then people say, ‘Well, we got to tear that down so that we can build something new.’ So it's not just like, ‘Oh, this is getting old, let's build something new.’ This is getting old for a reason because no one's taking care of it. Why aren't they taking care of it? Because all the owners have been incarcerated by the U.S. government through no fault of their own.

Hoffman: It's not one individual who has made this happen, but these are practices over time that certainly have benefited some and not others. One of the things we say about this in the book is that the erasure of some histories, in our area we can think of the Puyallup and the Coast Salish as well as Japanese Americans. The erasure of that history was actually necessary in order for certain types of developments to happen. We want to emphasize that preserving this history and thinking seriously about how this type of systemic erasure impacts individuals and communities in terms of their own sense of belonging to communities and to the United States should really be at the forefront of planners’ minds.

About Paw’d Defiance

The title of our show is more than just a clever play on words. The name reflects a philosophy, one that is committed to telling interesting stories about the people, research, initiatives, community partnerships and other issues related to UW Tacoma and higher education. It also speaks to our interest in the greater Tacoma community. Point Defiance is inexorably linked to the Grit City. Also, “defiance” is a fun word and, either intentionally or not, speaks to Tacoma's history as the “other” city in the Puget Sound region.

Thank you to Doug Mackey at Moon Yard Recording Studio for his recording support and Senior Lecturer Nicole Blair for our theme music. The first season of this podcast was made possible by funding from the UW Tacoma Strategic Initiative Fund.

You can find Paw'd Defiance on iTunes, Stitcher, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts and Spotify. You can also click here to listen: Paw'd Defiance

Main Content

Remembering Tacoma's Nihongo Gakko

UW Tacoma honors the story of the city's Japanese Language School with a memorial on campus, Maru, by Gerard Tsutakawa.

News Tags on this arrow_upward Story:

- Art

- Community support